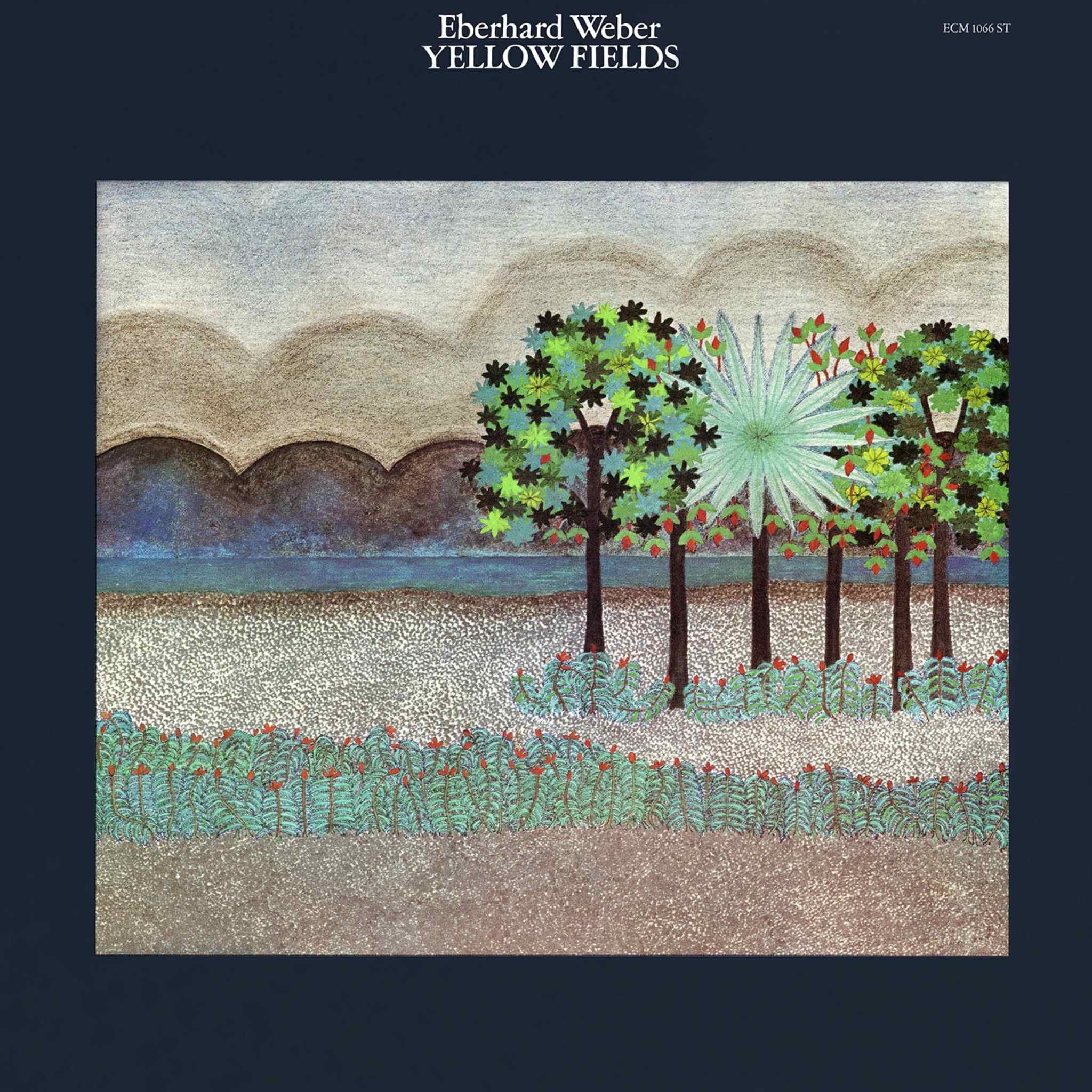

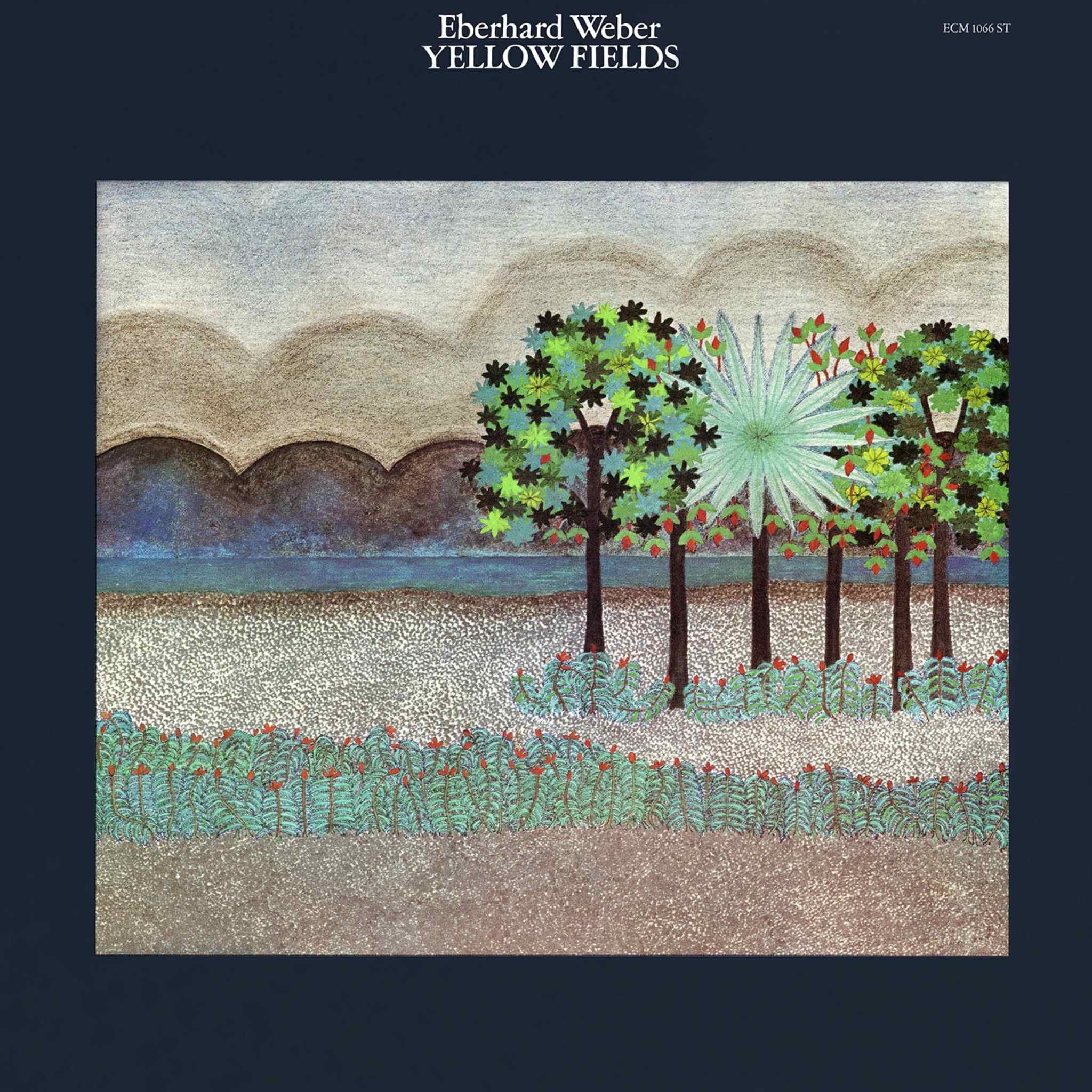

1975年に録音されたアルバム『イエロー・フィールズ』は、『ザ・ワイヤー』誌で「傑作」と称賛されました。これはエバーハルト・ウェーバー率いる『ザ・カラーズ』バンドの幕開けを告げるものであり、イアン・カーは同バンドを「当時最も形成的で影響力のあるグループの一つ」と評しました。ウェーバーの作曲は雰囲気とサウンドスケープを重視し、演奏者の技巧は副次的な役割にとどまりました。『インペタス』誌のインタビューで彼が明らかにしたように、ウェーバーはグループの相互作用と全体的なサウンドに大きな重点を置いていました。当時の伝統的なジャズとの差別化を図るため、ウェーバーはチャーリー・マリアーノのソプラノサックスを意図的に採用しました。この楽器は「ジャズ」という明確なイメージを最も喚起しにくいと考えていたからです。さらに、マリアーノがいつも使用していたアルトサックスの代わりに、ナグスワラムやシェナイといったインドの楽器を使用しました。