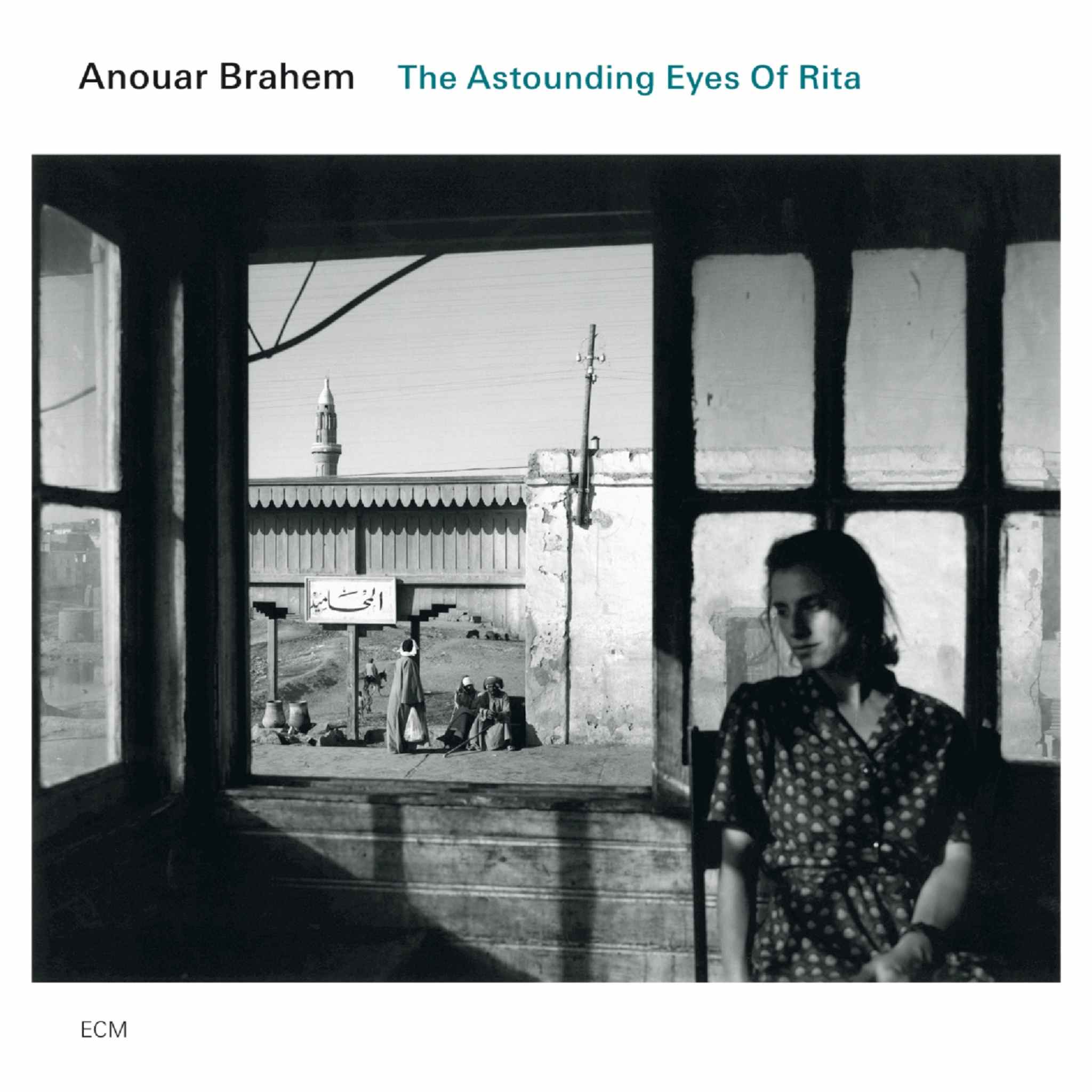

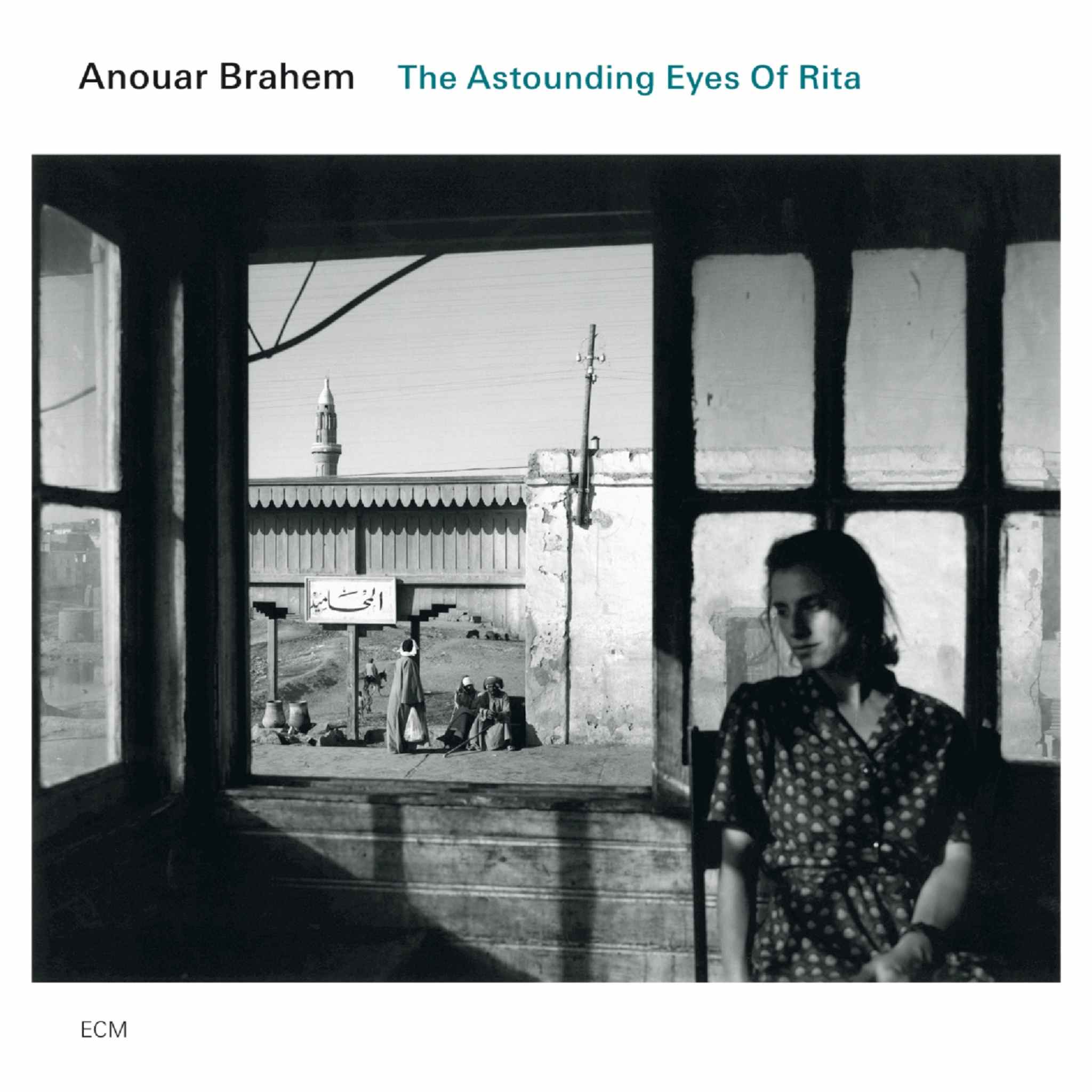

この魅力的なプロジェクトは、チュニジア出身のウード奏者、ブラームとプロデューサーのマンフレート・アイヒャーのコラボレーションによって実現しました。ウードとバスクラリネットの組み合わせはアヌアールの「ティマール」トリオを彷彿とさせますが、この東西の編成は「バルザフ」や「コンテ・デ・ランクロイヤブル・アムール」といったより伝統的なサウンドスケープに近いものです。クラウス・ゲシング(ノーマ・ウィンストンのトリオ所属)とビョルン・マイヤー(ニック・バーチュの「ローニン」所属)は、ジャズ以外の音楽的影響を受けており、ブラームの作品に見事に溶け込んでいます。レバノン出身のパーカッショニスト、カレド・ヤシンは、ダルブッカとフレームドラムで、温かくダークな音のダンスを繰り広げます。このアルバムは、パレスチナの詩人マフムード・ダルウィーシュに捧げられています。