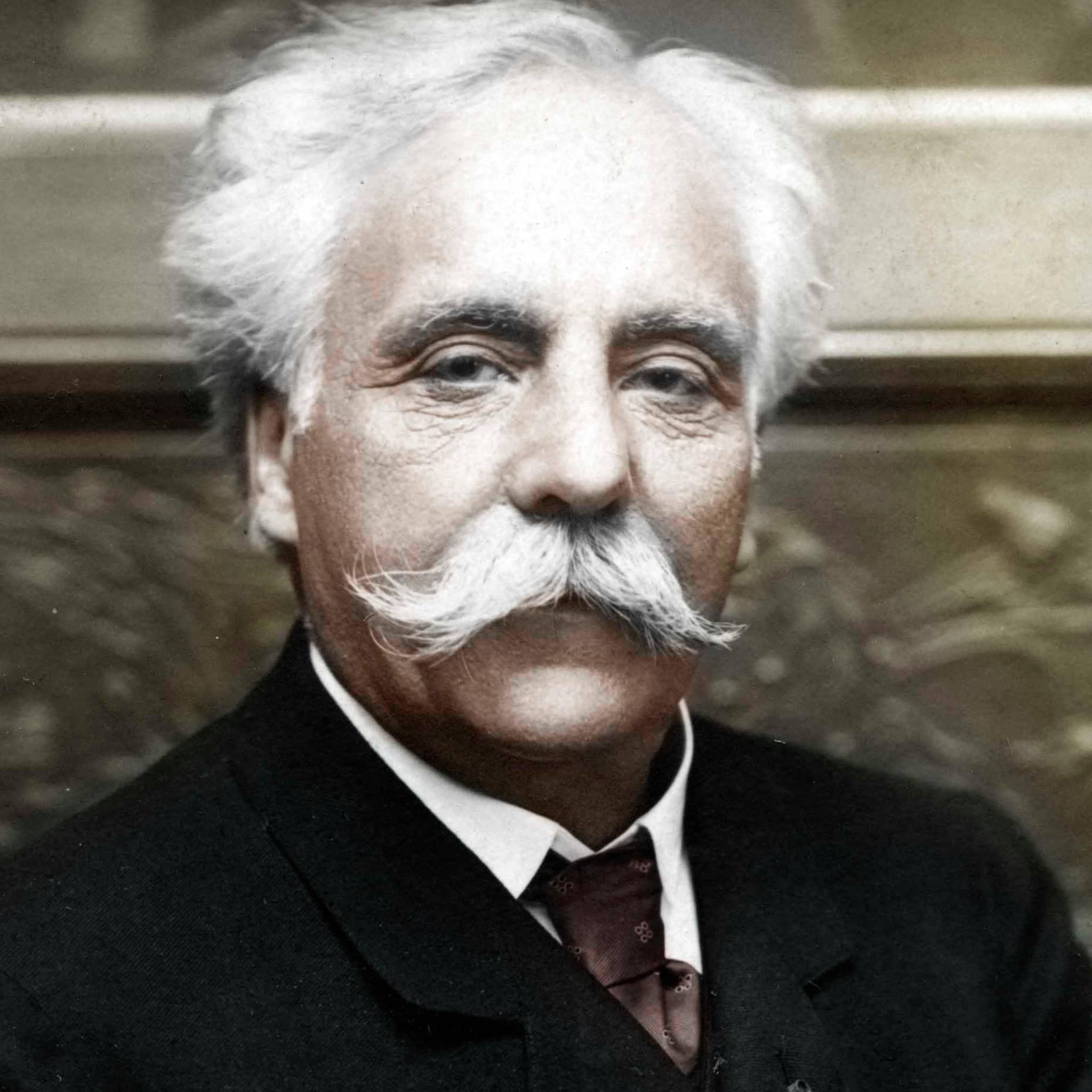

フランクの弟子であるヴァンサン・ダンディは、モーツァルトの重要な弦楽四重奏曲は、モーツァルトが既に33歳であった1789年と1790年に作曲されたものであり、青年期のものではないと指摘した。ダンディは、19世紀においてベートーヴェン後期の弦楽四重奏曲が中心的な役割を果たしたことを強調した。ドビュッシーとラヴェルが弦楽四重奏曲というジャンルを取り入れた時、ダンディはベートーヴェンとの繋がりが不可欠だと考えた。この点において、フランクの室内楽への傾倒、特に66歳で始めた弦楽四重奏曲は極めて重要であった。

フランクの革新への追求は、四重奏曲の力強い第一楽章に顕著に表れており、スケルツォは早期に完成している。ラルゲットはメンデルスゾーンを彷彿とさせる軽快さを反映している。フィナーレは、最初はベートーヴェンの交響曲第九番を引用しながら、その後独自の道を歩み始める。フランクの死後、ダンディはスコラ・カントルムを設立し、その価値観を後世に伝えることで、フランクの理想を守り続けました。フランクとフォーレは異なる見解を持っていましたが、共通の親密さと、それぞれが弦楽四重奏曲を遺作として残したいという願望によって結ばれていました。

フォーレの弦楽四重奏へのアプローチは、抑制と一貫した旋法的なスタイルを特徴としていました。彼の四重奏曲は、成熟した知的洞察と洗練された技術によって際立っています。明晰で瞑想的な性格と精緻に練られたリズムモチーフによって、フォーレは多様性の中にある統一性を体現する四重奏曲を創り上げました。ここで最も重要なのは過剰な装飾ではなく、むしろこのジャンルの根本的な基準である深い成熟です。