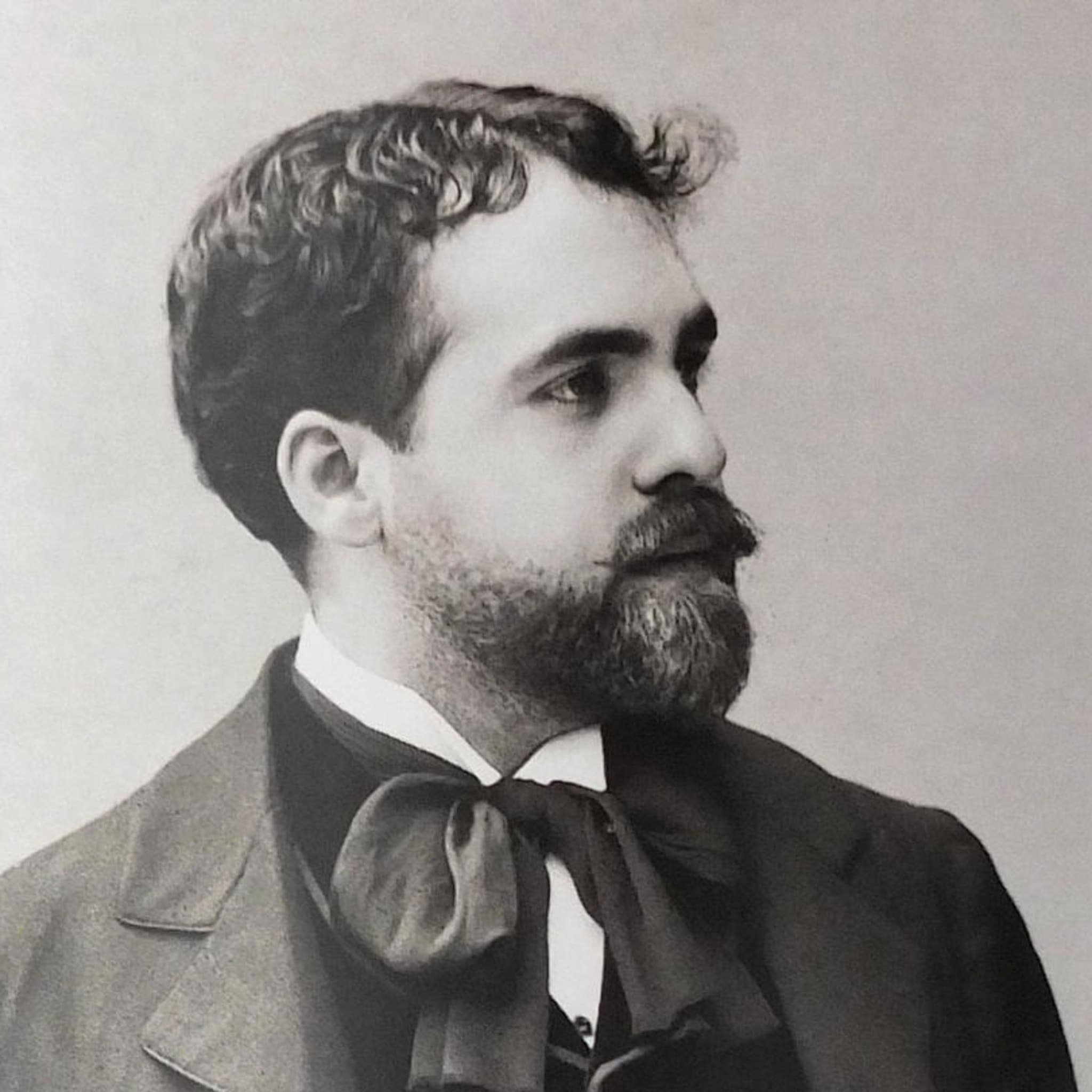

Reynaldo Hahn, am 9. August 1874 in Caracas, Venezuela, geboren, war ein französischer Komponist mit venezolanischer Herkunft. Als Sohn einer katholischen venezolanischen Mutter und eines jüdisch-stämmigen deutschen Vaters zog er in jungen Jahren nach Paris, wo er den Großteil seines Lebens verbrachte. Hahn entwickelte sich zu einem vielseitigen Künstler, der als Komponist, Dirigent, Musikkritiker und Sänger tätig war.

Bereits mit 14 Jahren erlangte er durch sein Lied "Si mes vers avaient des ailes" erste Bekanntheit und wurde zu einer prominenten Persönlichkeit der französischen Gesellschaft des späten 19. Jahrhunderts. Zu seinen engsten Freunden zählten Sarah Bernhardt und Marcel Proust, wobei die Verbindung zu Proust besonders prägend für sein Leben war.

Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, in dem er Militärdienst leistete, passte sich Hahn neuen musikalischen und theatralischen Strömungen an. In dieser Zeit feierte er Erfolge mit seiner ersten Operette "Ciboulette" (1923) und der musikalischen Komödie "Mozart" (1926), die er in Zusammenarbeit mit Sacha Guitry schuf.

Während des Zweiten Weltkriegs musste Hahn aufgrund seiner jüdischen Abstammung nach Monaco fliehen. 1945 kehrte er nach Paris zurück und wurde zum Direktor der Pariser Oper ernannt. Am 28. Januar 1947 verstarb Reynaldo Hahn in Paris im Alter von 72 Jahren.

Hahns musikalisches Schaffen war außerordentlich umfangreich. Er komponierte zahlreiche weltliche und geistliche Vokalwerke, lyrische Szenen, Kantaten, Oratorien, Opern, komische Opern und Operetten. Sein Werk umfasst außerdem Orchesterwerke wie Konzerte, Ballette, Tondichtungen sowie Begleitmusik für Theaterstücke und Filme. Darüber hinaus schrieb er Kammermusik und Klavierwerke. Hahn interpretierte seine eigenen Lieder sowohl gesanglich als auch am Klavier und machte Aufnahmen als Solist sowie als Begleiter anderer Künstler.

Obwohl sein musikalisches Erbe nach seinem Tod zunächst vernachlässigt wurde, erwachte seit dem späten 20. Jahrhundert ein wachsendes Interesse an seinen Kompositionen. Dies führte zu häufigeren Aufführungen vieler seiner Werke und Aufnahmen seiner Lieder, Klavierwerke, Orchestermusik und einiger seiner Bühnenwerke.