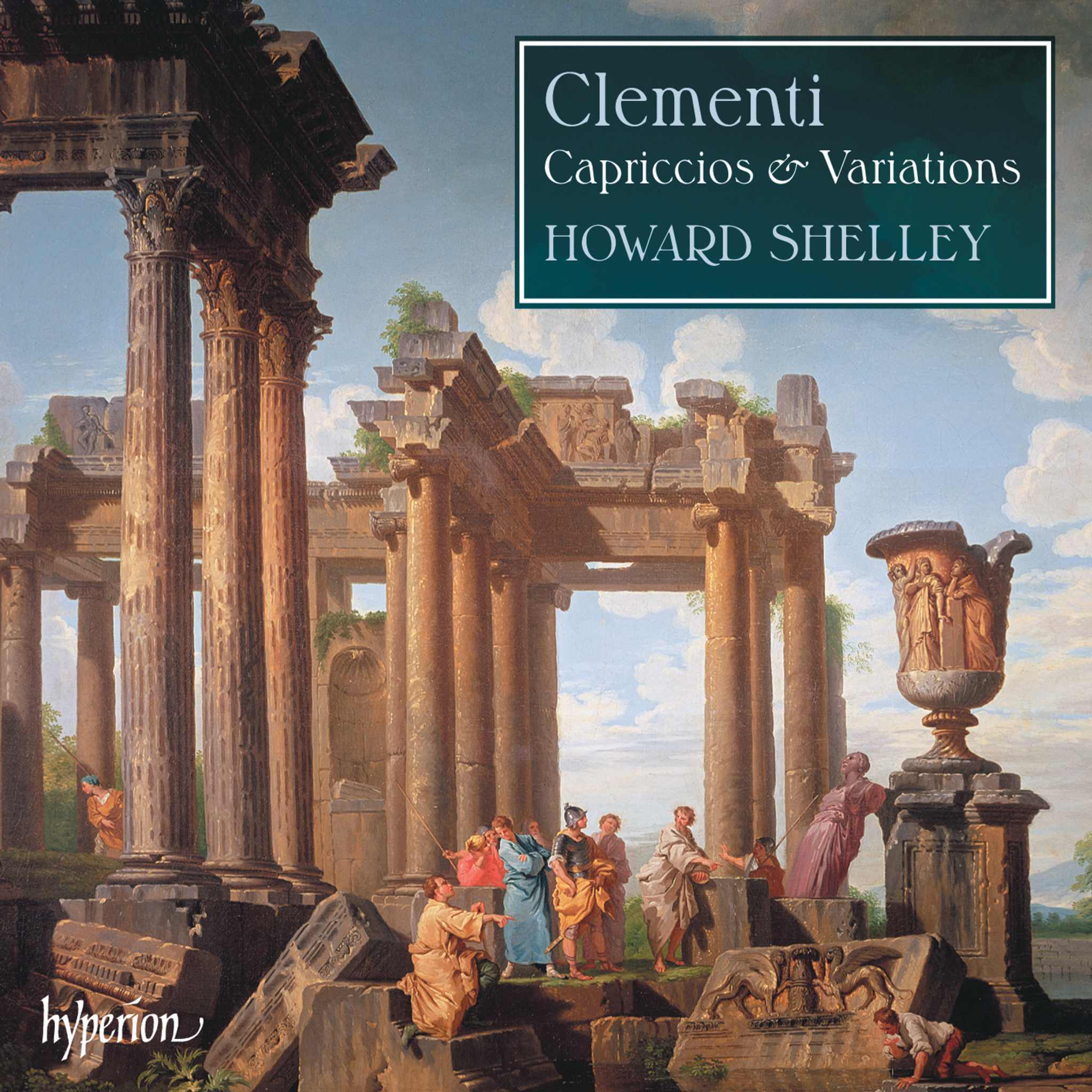

Muzio Filippo Vincenzo Francesco Saverio Clementi, born in Rome on January 23, 1752, the son of a respected silversmith, became a prominent Italian musician of his time. His exceptional musical talent was evident from a very young age—at just nine, he was appointed organist, and by twelve, he had already composed a mass. The young Roman was discovered by a passing English nobleman who engaged the 13-year-old as organist at his country estate in Dorset for seven years.

After his service in England, Clementi settled permanently in London in 1773, where he quickly rose to become a leading figure in the city's musical life. A remarkable event in his career was a piano contest with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on December 20, 1781, before Emperor Joseph II, in which both artists captivated the audience. Despite Clementi's undeniable abilities, Mozart is said to have criticized his playing as too mechanical.

After his last public performance as a pianist in 1786, Clementi turned to new pursuits. He worked successfully as a music dealer, publisher, and instrument maker, amassing a considerable fortune. His publishing house released works by important contemporary composers such as Beethoven, Wesley, and Moscheles, though interestingly, neither Mozart nor Haydn appeared in his catalog.

Although he had ended his active career as a pianist, Clementi continued to compose. His symphonies, published in 1823 and 1824, brought him his last major successes before his death on March 10, 1832, in Evesham, England.