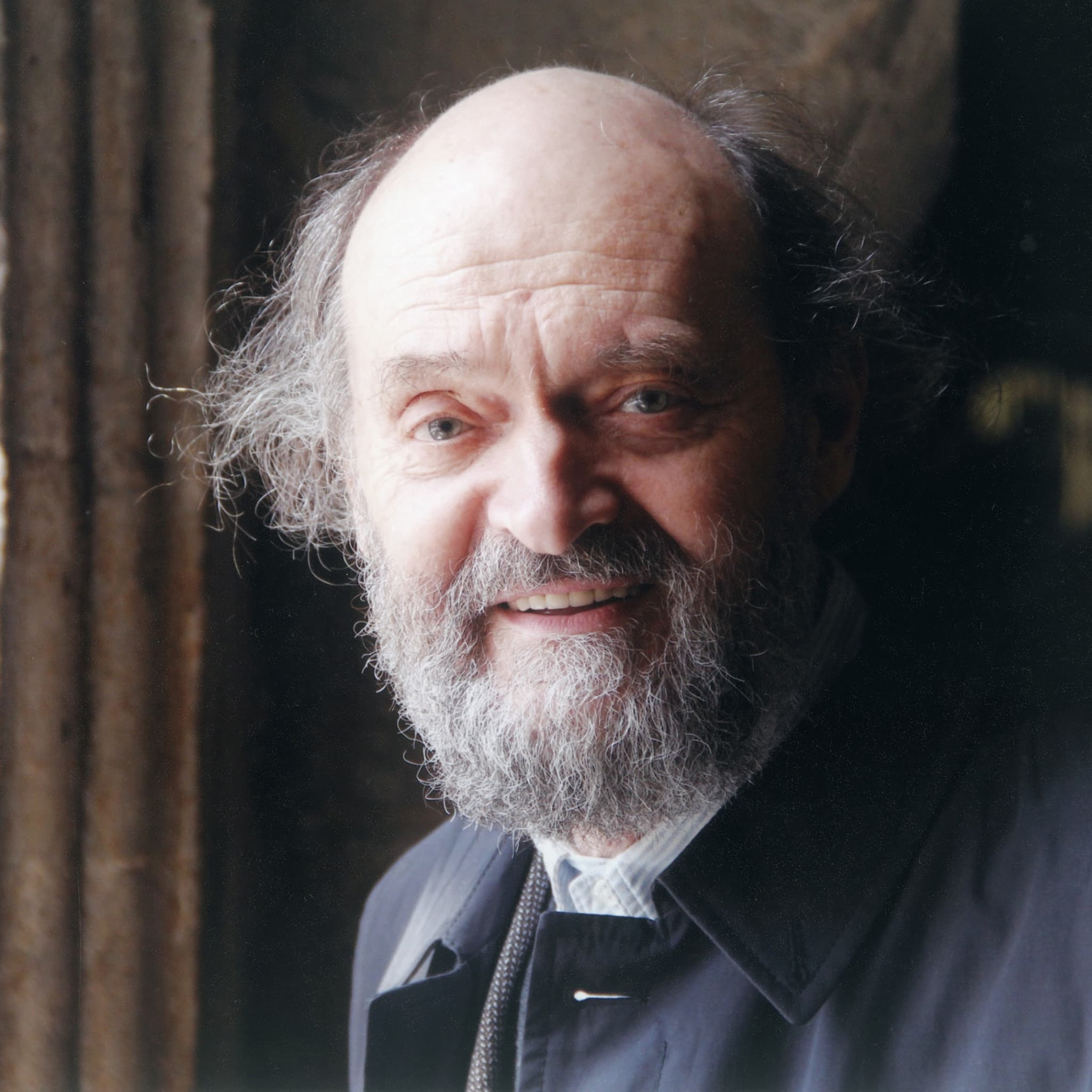

アルヴォ・ペルトの音楽は、美学、倫理、そして精神性の繋がりを求める、人間の根源的な欲求を鮮やかに描き出します。現代社会において、この欲求はしばしば政治や経済に従属させられがちです。彼は2007年、ゲルリッツとズゴジェレツ両市から国際橋梁賞を受賞し、この評価を得ました。彼の新作『イン・プリンチピオ』は、近年の音楽がまさにこの繋がりを体現していることを示しています。四半世紀前、ECMはペルトの「タブラ・ラサ」でニュー・シリーズを開始しました。そして今、マンフレート・アイヒャーが再びプロデュースを手掛けたこの作曲家12枚目のアルバムには、約10年にわたる様々な長さの作品6曲が収録されています。そのうち4曲は初めてCD化されます。これらの緻密な演奏は、ペルトの音楽に長年精通してきた指揮者、トーヌ・カリユステの指揮の下、エストニアのアンサンブルによって録音され、作曲者自身が全曲伴奏を務めています。

《プリンチピオ》において、ペルトの音楽はまさに折衷的な融合と言えるでしょう。その様式の多様性は印象的です。ペルトは、1970年代半ばに独自のスタイルを確立して以来、追求してきた表現手段を巧みに融合させています。親密な要素と記念碑的な要素が共存し、コード進行は劇的なクライマックスへと盛り上がります。彼の作品における転調は常に、その根底にある感情的な意味に基づいています。《プリンチピオ》は、ヨハネによる福音書の冒頭の詩句「初めに言葉ありき」を5部構成にしたものです。哀歌的な管弦楽曲「ラ・シンドーネ」は、トリノの聖骸布をまとったキリストのイメージを想起させます。ローマ聖年2000年を記念して作曲された「ローマの聖母マリア、チェチーリア」は、殉教者であり音楽の守護聖人であるチェチーリアに捧げられています。平和への静かな嘆願、亡くなった友人の思い出、そして人生の浮き沈みに対する思いが、ペルトの音楽の魔法を体現する、比較的短いこの 3 つの曲の感情の旅を形成しています。