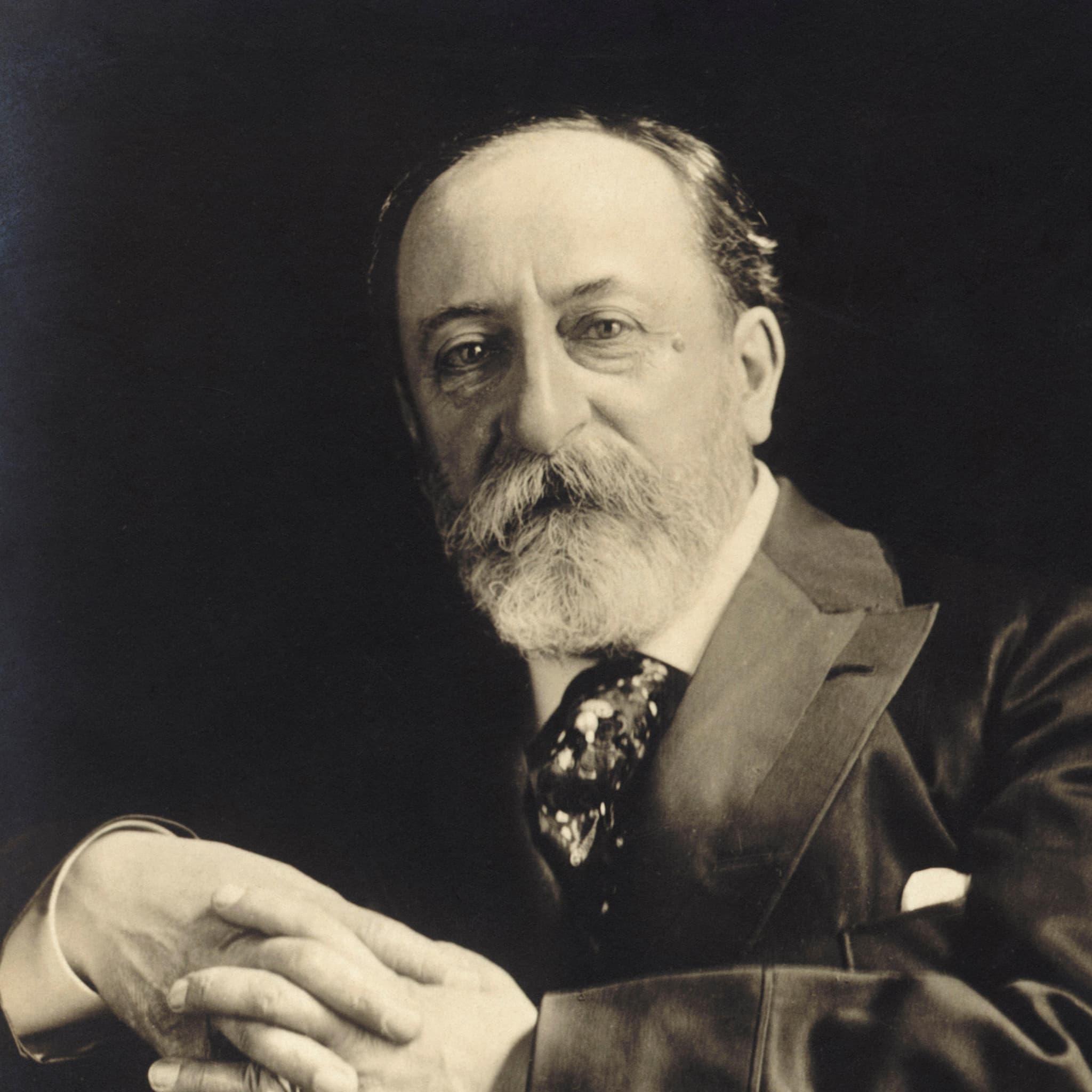

A thorough examination of Charles Camille Saint-Saëns' career illuminates his achievements as a composer and pianist, as well as the challenges he faced. His works received mixed reviews from critics, some lamenting the lack of youthful enthusiasm that might have forged a distinctive artistic identity. Biographical difficulties, such as failing to win the Prix de Rome, did not, however, diminish his artistic versatility. His Symphony "Urbs Roma" remains enigmatic—both in its Roman title and its musical structure. Although some of his compositions, like this 1856 symphony, were never published, his artistic legacy remains fascinating for future generations due to its distinctive characteristics.

In his Symphony in F major of 1856, Saint-Saëns impressed with symphonic brilliance, featuring lyrical passages, skillful use of motifs, and harmonic shifts. Despite certain critical shortcomings, the work's variations reveal his refined sense of musical expression. His artistic aspirations and structural concepts may have reached their culmination in the Symphony in A minor of 1858–59, before he abandoned this compositional form until 1886. The dedication of this symphony to Jules Pasdeloup and its performance demonstrate Saint-Saëns' creative talent and his keen sense for musical innovation.

Saint-Saëns' compositions contributed significantly to the development of the symphonic genre in France, although Berlioz and Franck had already explored similar avenues. In his symphonic poems, he skillfully incorporated mythological themes and Romantic horror. With his "Danse macabre" of 1873, he created a powerful sonic experience that elicited both admiration and criticism. Saint-Saëns' extensive oeuvre, ranging from complex works to the lighthearted "Carnival of the Animals," demonstrates his exceptional musical talent, which was later also recognized by Debussy.

The reception of his works ranged from incomprehension to enthusiastic acclaim. Saint-Saëns' artistic contribution represents an important chapter in the history of French music, characterized by versatility and innovative power.