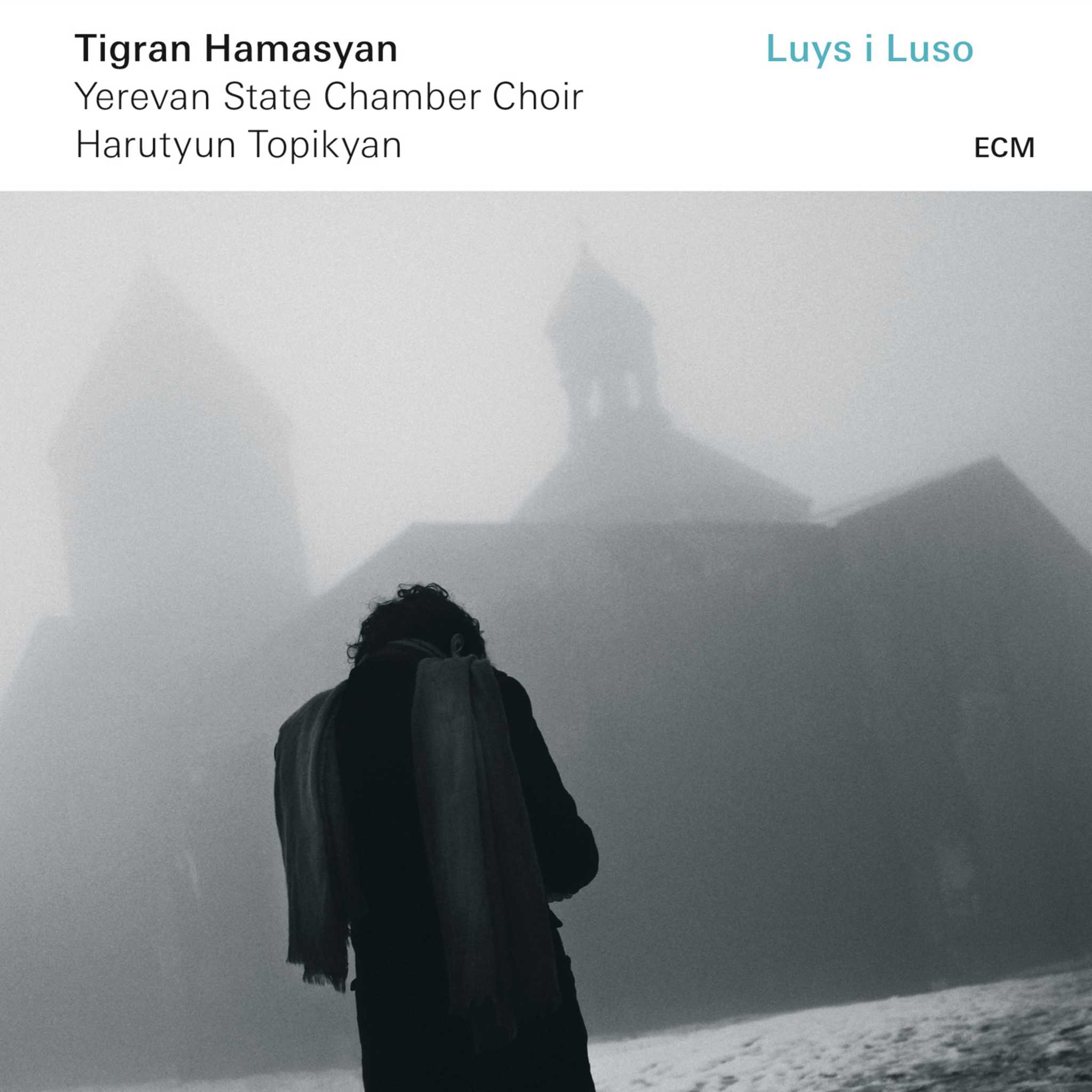

With his first album on ECM, Tigran Hamasyan impressively explores Armenian sacred music. For this project, he selected hymns, sharakans, and chants by renowned composers such as Grigor Narekatsi, Nerses Shnorhali, Mesrop Mashtots, Mkhitar Ayrivanetsi, Grigor Pahlavuni, Komitas, and Makar Yekmalyan, rearranging them for piano and vocal ensemble. The works, composed between the 5th and 19th centuries, acquire a new, dramatic dimension through Hamasyan's creative improvisations and the expressive singing of the Yerevan State Chamber Choir. The recording of 'Luys i Luso' (Light from Light) took place in Yerevan in October 2014, conducted by Manfred Eicher.

[The recording of 'Luys i Luso' (Light from Light) was made in Yerevan in October 2014.] In March 2015, Hamasyan and the Yerevan State Chamber Choir embarked on an extensive concert tour through numerous churches in Armenia, Georgia, Turkey, Lebanon, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Czech Republic, England, Germany, Luxembourg, Russia and the United States to promote Armenia's musical heritage internationally.