Duration132 Min

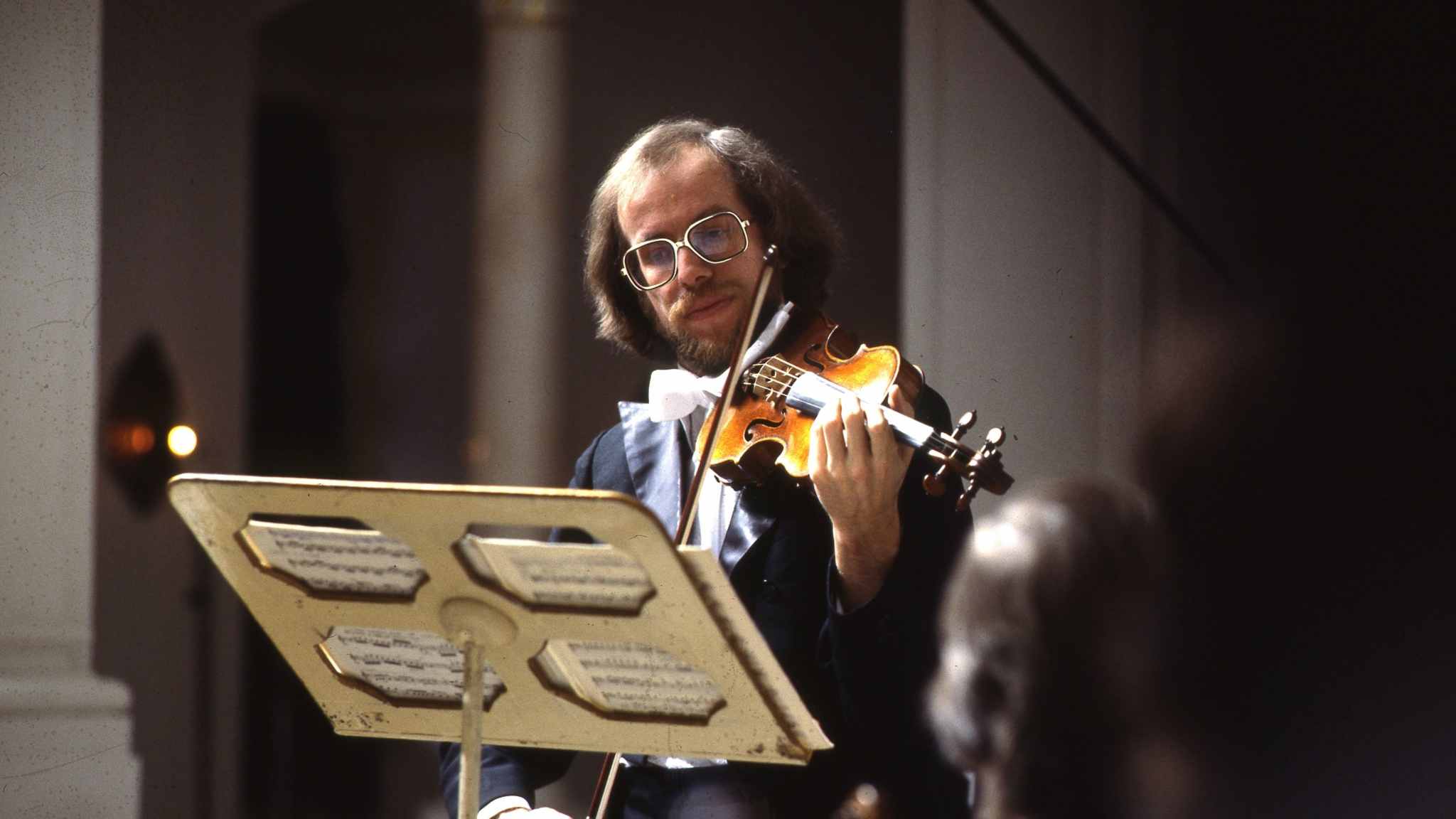

Bach: The Sonatas and Partitas for Violin Solo

Gidon Kremer

Duration132 Min

Johann Sebastian Bach

Sonata No. 1 for Solo Violin in G Minor, BWV 1001

Johann Sebastian Bach

Partita No. 1 for Solo Violin in B Minor, BWV 1002

Johann Sebastian Bach

Partita No. 1 for Solo Violin in B Minor, BWV 1002

Johann Sebastian Bach

Partita No. 1 for Solo Violin in B Minor, BWV 1002

Johann Sebastian Bach

Sonata No. 2 for Solo Violin in A Minor, BWV 1003

Johann Sebastian Bach

Partita No. 2 for Solo Violin in D Minor, BWV 1004

Johann Sebastian Bach

Sonata No. 3 for Solo Violin in C Major, BWV 1005

Johann Sebastian Bach