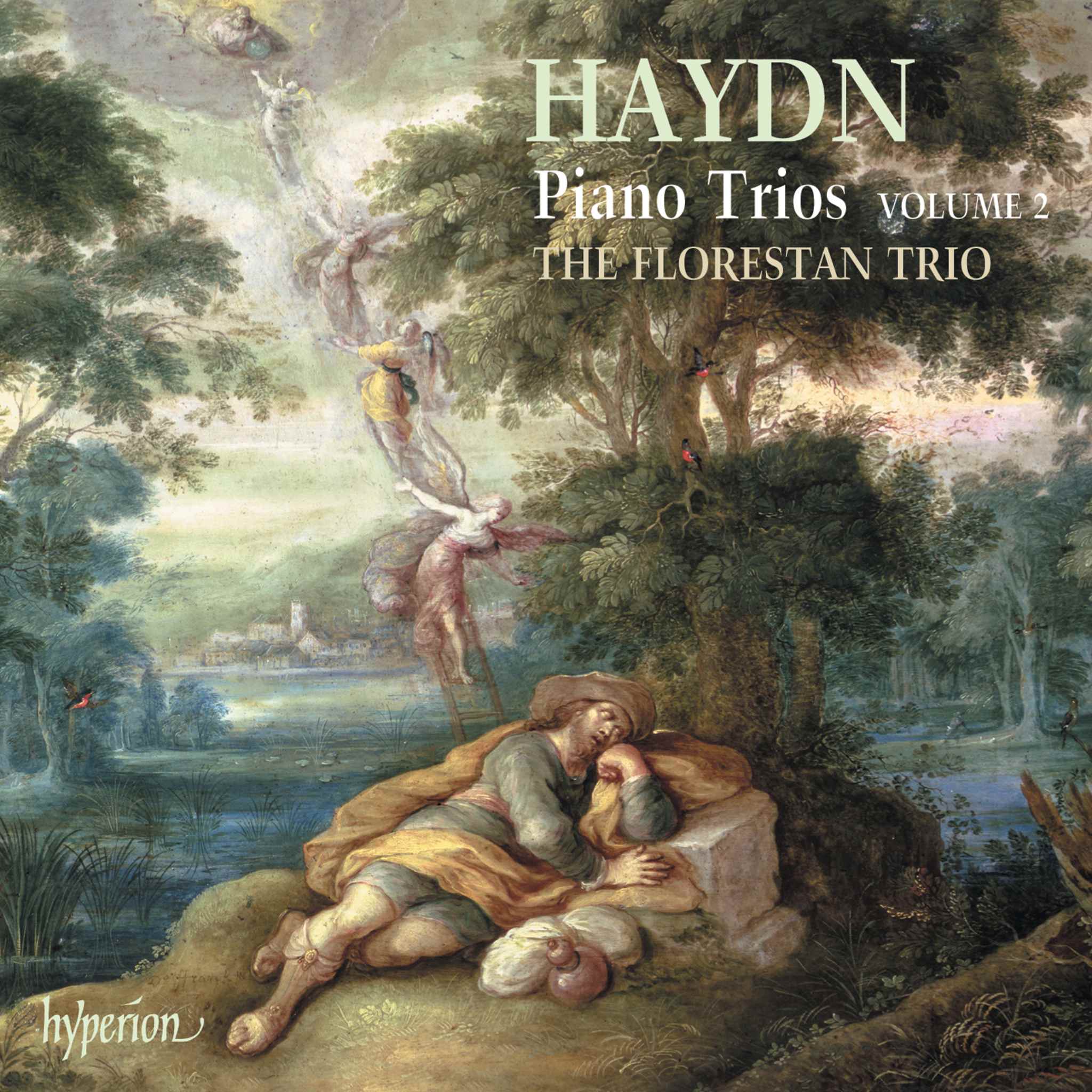

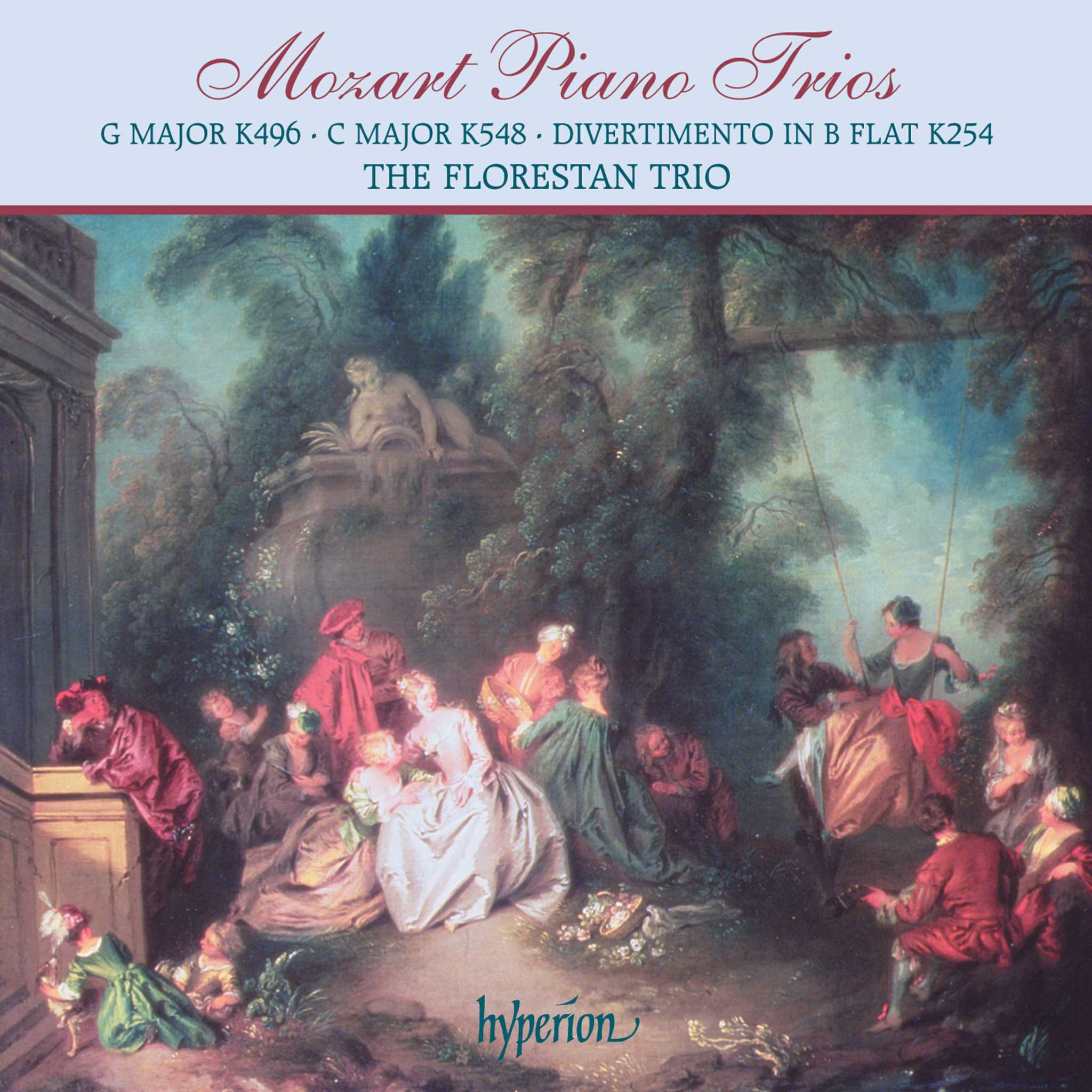

このCDには、作曲家たちの人生の異なる時期に作曲された3つの三重奏曲が収録されています。1つは若き日、もう1つは40歳前後の晩年、そして3つ目は77歳の作曲家によって書かれたものです。これらの作品は音楽的表現が大きく異なり、その違いは作曲家の名前だけにとどまりません。それぞれの三重奏曲は、それぞれの作曲家の作品の中で独自の位置を占めています。

クロード・ドビュッシーは10歳でパリ音楽院に入学しました。両親は彼のピアニストとしての才能によって窮地から抜け出せると期待していました。ドビュッシーは音楽院で当初は成功を収めましたが、すぐに自分が有名なピアニストになることはおそらくないだろうと悟りました。

ドビュッシーのピアノ教師は、チャイコフスキーの後援者であった女性に彼を推薦しました。女性は子供たちと旅に同行するピアニストを探していたのです。ドビュッシーは旅に出ましたが、実年齢よりも若く見えることもあったのです。いくつかの意見の相違はあったものの、ドビュッシーの音楽的才能と音楽性は高く評価され、称賛されました。

メック夫人はドビュッシーに子供たちにピアノを教え、旅の音楽に同行するよう命じました。時折批判もありましたが、ドビュッシーの初見演奏能力と器楽演奏の卓越性は特に高く評価されました。彼の音楽は「誇張のない感情」を伝えることを目指していました。

一行はアルカションからフィレンツェへと旅し、途中で様々な都市を訪れました。この間、ドビュッシーは新しい曲を作曲し、他の音楽家と交流しました。チャイコフスキーはドビュッシーの作品を高く評価し、メック夫人をはじめとする他の人々を尻目に、彼の音楽活動を支援しました。

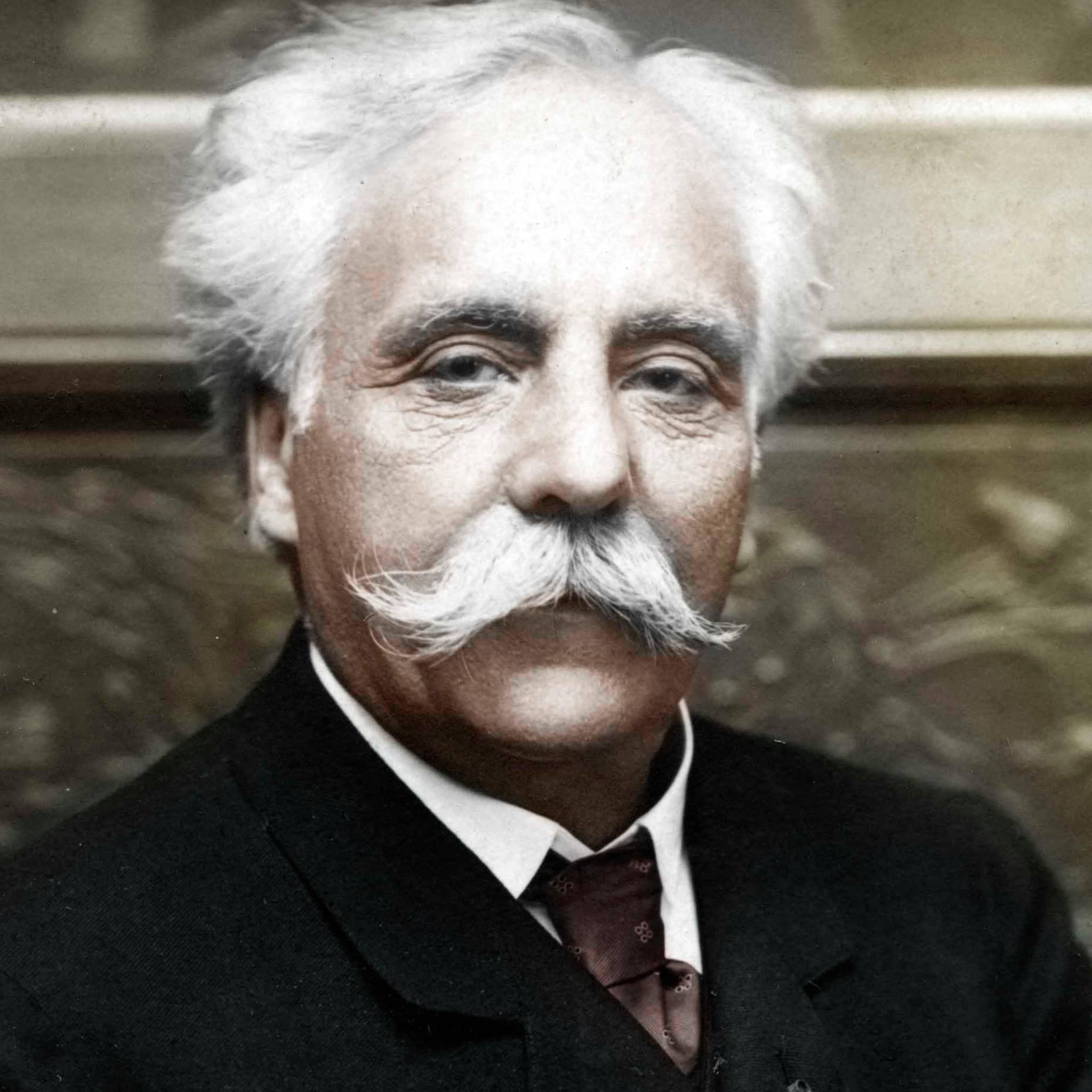

サロン作曲家と称されることの多いガブリエル・フォーレは、同時代の多くの作曲家ほど音楽の流行に左右されませんでした。音楽界では、彼の反骨精神に満ちた作品を完全に理解する人は多くありませんでした。外部からの拒絶にもかかわらず、フォーレの作品は独特の才能と一貫性を示していました。

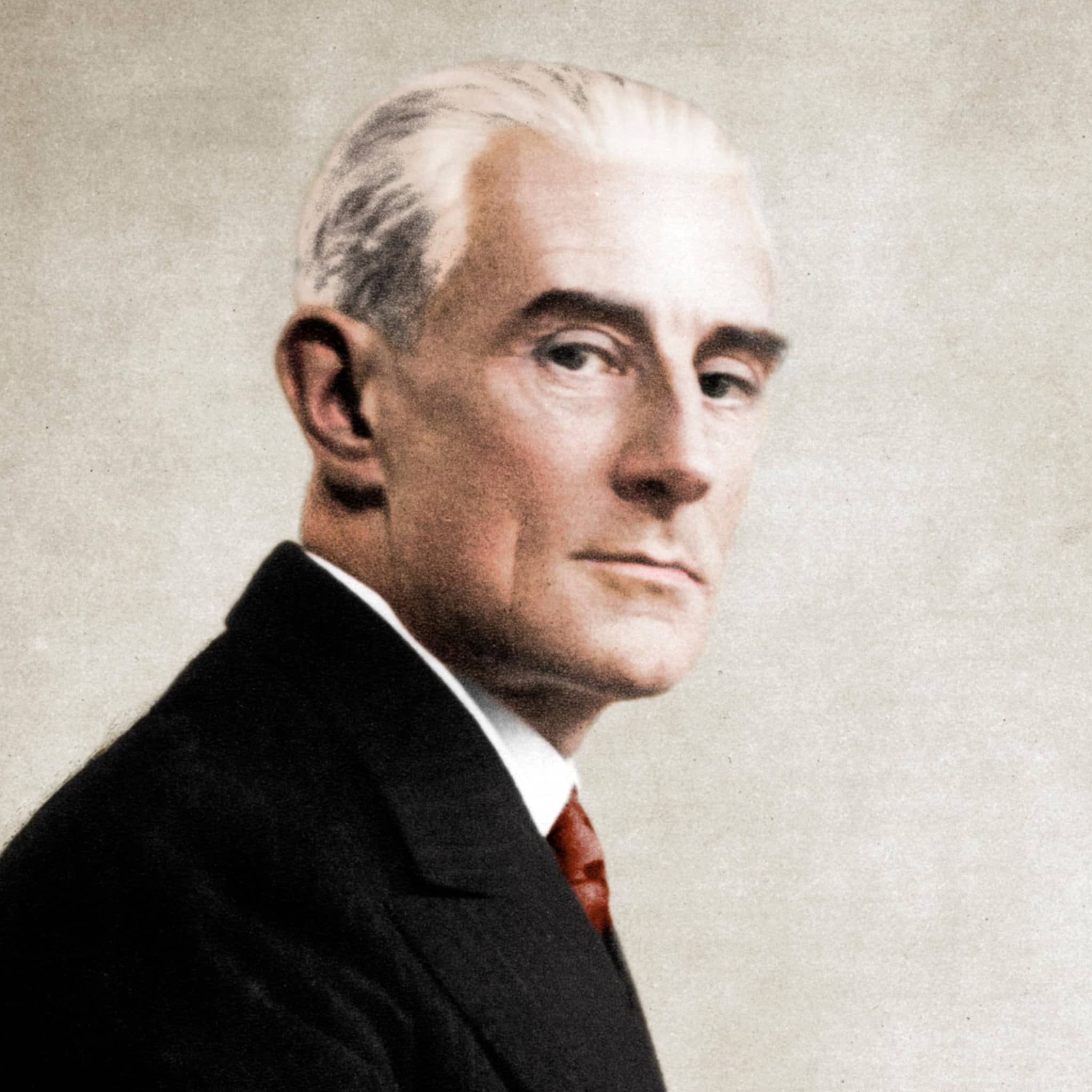

フォーレのピアノ三重奏曲とラヴェルの三重奏曲は、作曲への異なるアプローチを体現しています。フォーレの音楽は繊細なニュアンスと躍動感に特徴づけられるのに対し、ラヴェルはパントゥムやパッサカリアといった明確な形式を用いています。どちらの作曲家も、独自の解釈と表現手法を作品に注ぎ込んでいます。

ラヴェルとフォーレは三重奏曲の作曲において、それぞれ異なる重点を置いていました。ラヴェルは構造化された、緻密な作曲様式を好みましたが、フォーレは音の移ろいや繊細な変化に重点を置きました。両作曲家の作品には、数多くの技術的、芸術的な革新が見られます。