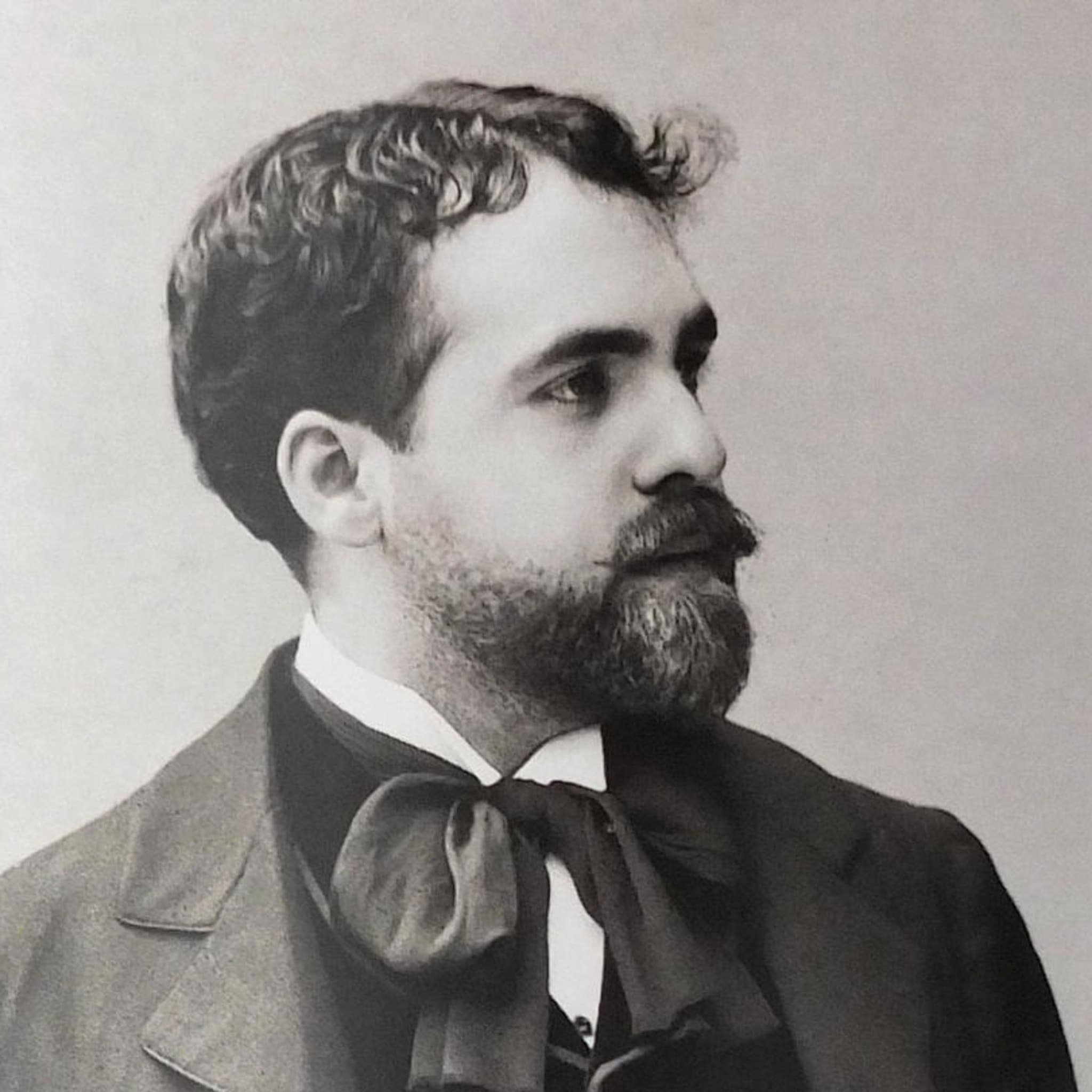

フランシス・プーランクとレイナルド・ハーンは25歳も歳が離れていましたが、多くの共通点がありました。ハーンはベネズエラ出身で、後にフランス国籍を取得しましたが、二人はパリの社交界で完璧なスタイルで活動し、演劇音楽への情熱を共有し、バレエ、オペラ、オペレッタを創作しました。[3][4] ハーンのマルセル・プルーストとの親密な関係や、プーランクの特定の社会集団への親近感など、二人の社交や特別な関心は、当時の文化界でよく知られていました。[3]

プーランクのバレエ「オーバード」の音楽は、ノアイユ子爵夫妻の委嘱により作曲され、1929年の仮面舞踏会で初演されました。この作品は、永遠の処女を運命づけられた神話上の狩人ディアナの運命を描いています。ホルンとトランペットの音色が奏でるこの作品は、田園的な雰囲気を醸し出し、情熱、絶望、そして移り変わる旋律に特徴づけられる内的ドラマを通してヒロインを優しく包み込みます。対照的に、プーランクのシンフォニエッタは、特定のプログラム的背景を持たない、明るく軽快な作品です。[3]

一方、レイナルド・ハーンは「ベアトリス・デステの舞踏会」を作曲しました。この作品は、特定のプログラム的内容を持たない作品です。ハーンは興味深い楽器編成を好むことで知られ、パリやイギリスの社交界と密接な関係を維持していました。[3][4] 彼の音楽は、過ぎ去った時代の雰囲気を喚起し、イタリアの貴族の宮殿で祝宴を催した夜を思い起こさせます。

両作曲家の優雅な作風には、しばしば根底にメランコリーが潜んでいます。プーランクは多様な音楽的表現力を発揮するのに対し、ハーンの音楽は深い憧憬と郷愁を反映しています。両者ともスタイルは異なるものの、フランスの音楽界に永続的な影響を与え、それぞれの分野の重要な代表者と考えられている[3][4]。