Countries. Roguenet. While French airs aim for gentleness, suppleness, flow, and cohesion, the Italians rely on surprising dissonances and bold cadences. The distinctive character of Italian music makes it incomparable to works from other countries. Roguenet described the musical contrasts between the two nations in the early 18th century. During the reign of Louis XIV, the magnificent music of the royal chapel was paramount, before musical trends shifted. Couperin's works stand out significantly from the usual compositions at Versailles and show a stronger affinity with the Italian style.

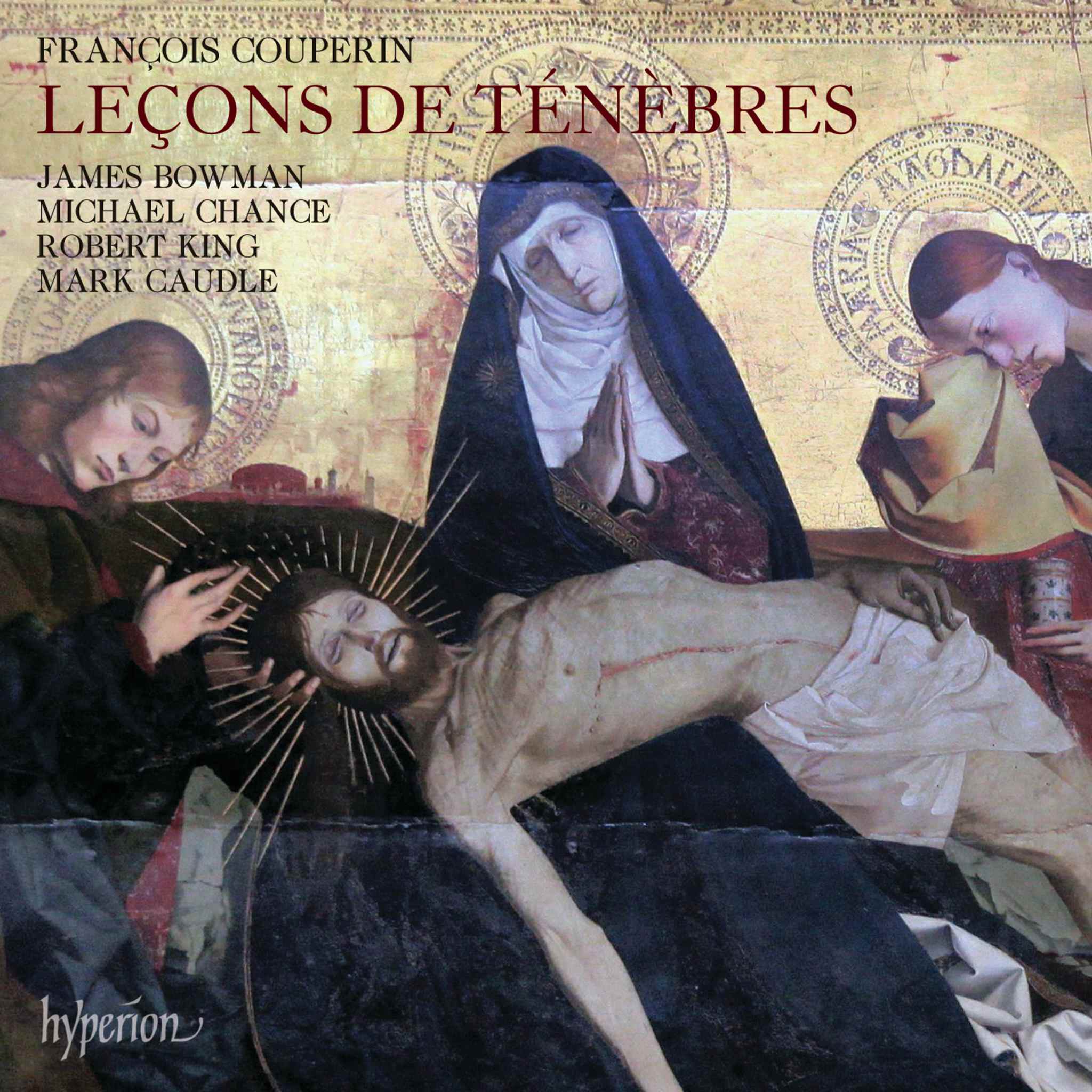

Couperin's sacred music, especially the Trois Leçons de Ténèbres (Three Lessons of Darkness), is characterized by a personal touch and originality. These pieces depict the suffering of Jeremiah with extraordinary expressiveness and intensity. The Leçons vary in instrumentation: the first two are solo pieces, while the third is a duet. Three works from Couperin's early years are preserved in the Bibliothèque Municipale in Versailles. The motet in honor of Saint Bartholomew is Italianate in style, combining dramatic expression with rich harmonies. Couperin's Magnificat impresses with its inspiring structure and eleven contrasting sections, each lasting several minutes.