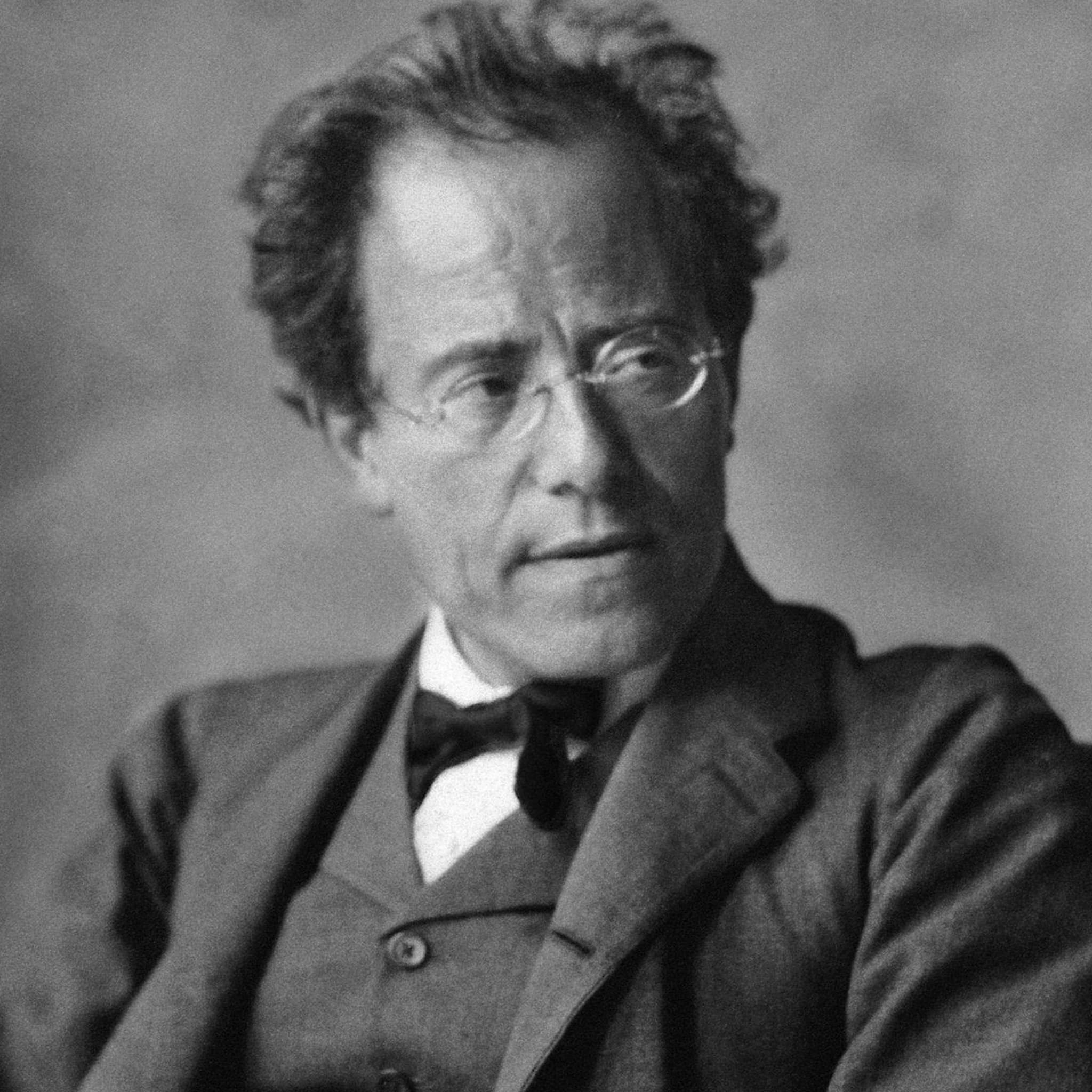

AboutGustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler is still a pulse-taker of our time. In his works, we discover the darkest sides of our soul. Postmodernism in music began with him.

By Axel Brüggemann

Upstairs, in his "Studi," in the composing hut on the alpine pastures at the edge of Lake Wörthersee, it was quiet: at most, the cries of playing children, perhaps a cowbell, or the rustling of the wind reached Gustav Mahler's ears. Up here, the air was free from the turbulent hustle and bustle in the valleys, from the barking demonstrations, the roaring rhythms of the night bars, from the rattling factories where new weapons and brassieres were being invented. Up here, in the sound-vacuum of the mountains, Mahler could reorder the noise of his world. When he descended back into the world of concert halls, he shocked his audience, who were dancing on a volcano, with timpani and trumpets. Music history often classifies Gustav Mahler as a late Romantic, because he raved about Weber and Wagner and brought their sound philosophy to its conclusion. Today, we know that Gustav Mahler was actually a postmodern composer, one who understood the sounds of the world as a self-service store, one who undermined the order of the classical symphony through eclecticism, for whom musical motifs were at most associative fragments of memory, for whom the actual musical language originated not in the orchestra but in the minds of the listeners. Gustav Mahler is the child of a crazy time. Europe was on the brink of the First World War, and Sigmund Freud was trying to fathom the deranged souls of people on his couch in Vienna.

Watch concerts and operas by Gustav Mahler on STAGE+

Soundtrack of Psychoanalysis

Mahler's compositions were the accompanying music of the age of extremes. In his symphonies, cowbells chime, fairground music clatters, one hears marches and waltzes. But in contrast to the sounds on the street, Mahler's music, which he composed in the stillness of the mountains, no longer sounded cheerful – it was a melancholic, yearning dance of death. He placed falling sighing seconds next to jubilant natural fourths, mixing the music of Schopenhauer's stages of being with "La Paloma" skirmishes. Without an ornate buffer zone, the glorious major-key world crashed into unspeakable minor-key tristesse. Once, at a fair, Mahler cheered: "That's polyphony – that's where I got it from!"

His scores are crammed with familiar elements, memories, and effects; his Ländler almost come to a halt, his marches stomp angrily, and for his wild fairground music, no carousel seems to spin fast enough. Mahler placed the noises of his everyday life into new contexts – everything became a memory, everything linked to everything else, everything was association. A gigantic, psychological sound play.

"He predicted everything"

The realization that Gustav Mahler was not only a child of his time but also explored the eternally valid soul of modern man in his music, that he illuminated the dark corners of imagination and poked at the flesh of our bodies, we owe largely to Leonard Bernstein. Like no other conductor before him, he embodied Mahler's music, not merely conducting it but suffering through it, driving his orchestras not to beautiful playing but to snorting, dancing, hoping, and suffering. Especially the Second, the "Resurrection Symphony," Bernstein elevated to a great world theater, with which he even commemorated the assassinated US President John F. Kennedy.

Bernstein discovered in Mahler both the widescreen of Hollywood and the complex structures of chamber music – he proved that Mahler is our contemporary. "Only now, after we have gone through almost everything," Bernstein once said, "the smoking chimneys of Auschwitz, the senseless bombings of the Vietnamese jungles, the assassination of Kennedy, South African racism, the Arab encirclement of Israel, the arms race – only now do we understand Mahler's music, understand that he predicted everything."

Current Remembrance

Mahler's music is always there; it has itself become a memory of that time when man became modern and his psyche became a category of his existence. Visconti elevated the Adagio of the Fifth Symphony to a leitmotif in "Death in Venice," and even "Hannibal Lecter" murders to Mahler.

Meanwhile, Mahler interpretations have become a kind of pulse-taker of the present. Sir Georg Solti analyzed their structures, Pierre Boulez presented him as Schoenberg's father, and Simon Rattle beamed him into postmodernism as an eclectic. But Bruno Walter, Claudio Abbado, and Riccardo Chailly also show that the Mahler renaissance is unstoppable. They all seek their own perspectives on our chaotic world when they begin to order Mahler's sound panopticon. The interpretation of his symphonies has become the soundtrack of our society; they reveal how the world ticks, how great the schizophrenia of civilized society is between dark abysses and dazzling hopes. The conductor Rafael Kubelik once said: "Beethoven is always called Prometheus; he wanted to bring heaven to mankind. For the future, I see this mission in Mahler's works."

An Outsider as a World-Understander

Gustav Mahler was only one meter and sixty centimeters tall. He was quite ugly, had a high forehead, and suffered from hemorrhoids. Nevertheless, he impressed the people he met. His alert eyes, his melancholy, his quirky humor captivated people. Mahler was always a minority: as a Bohemian among Austrians, as an Austrian among Germans, as a Jew throughout the world. And: he was a broken man. Six of his 11 siblings died in childhood, his parents also died early, and he had to take care of his siblings. After he composed Rückert's "Kindertotenlieder," his daughter Anna Maria died of scarlet fever – Mahler requested an audience with Freud. Perhaps only someone like him could write this music, an outsider who observed the world not from the eyes of the masses, but from his own, wounded, anxious heart.

From Sound-Vacuum to Noise

His wife Alma Schindler called Mahler her "amok runner" because he wanted to dismantle the whole world with his musical temperament. He inspired Zemlinsky, Schoenberg, Berg, and Shostakovich and laid the foundations for New Music. As an opera director, he personally promoted every musical revolution, for example, when he championed Richard Strauss's "Salome," which was banned by the stuffy Viennese opera audience. Mahler wanted to tell the future of humanity through music when the established bourgeoisie had not yet grasped that a new era had long since dawned. To this day, Gustav Mahler is probably one of those composers who ushered in a new era of classical music, who radically continued the conventions of classicism and romanticism, who gave the age of extremes a new sound. In his works, a world gone mad, full of hopes, dances straight into melancholy. So where are we when we listen to Mahler today? Where does his composer's hermitage truly lie? Perhaps somewhere on the borders of world and time, of dream and reality. From his alpine sound-vacuum, Gustav Mahler created music that still defines the hustle and bustle of our world today.