Concerts and Operas

Albums

Appears On

Documentaries

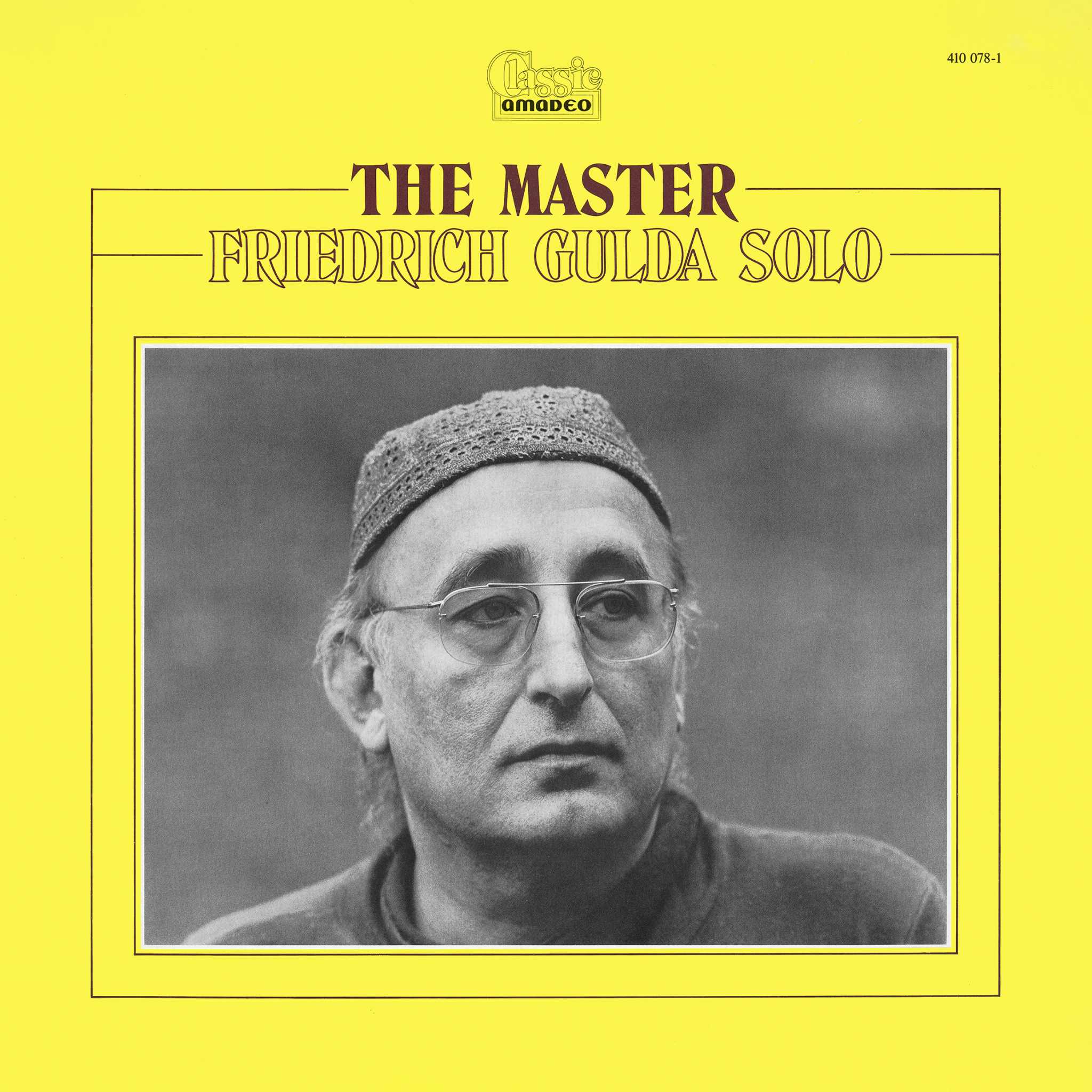

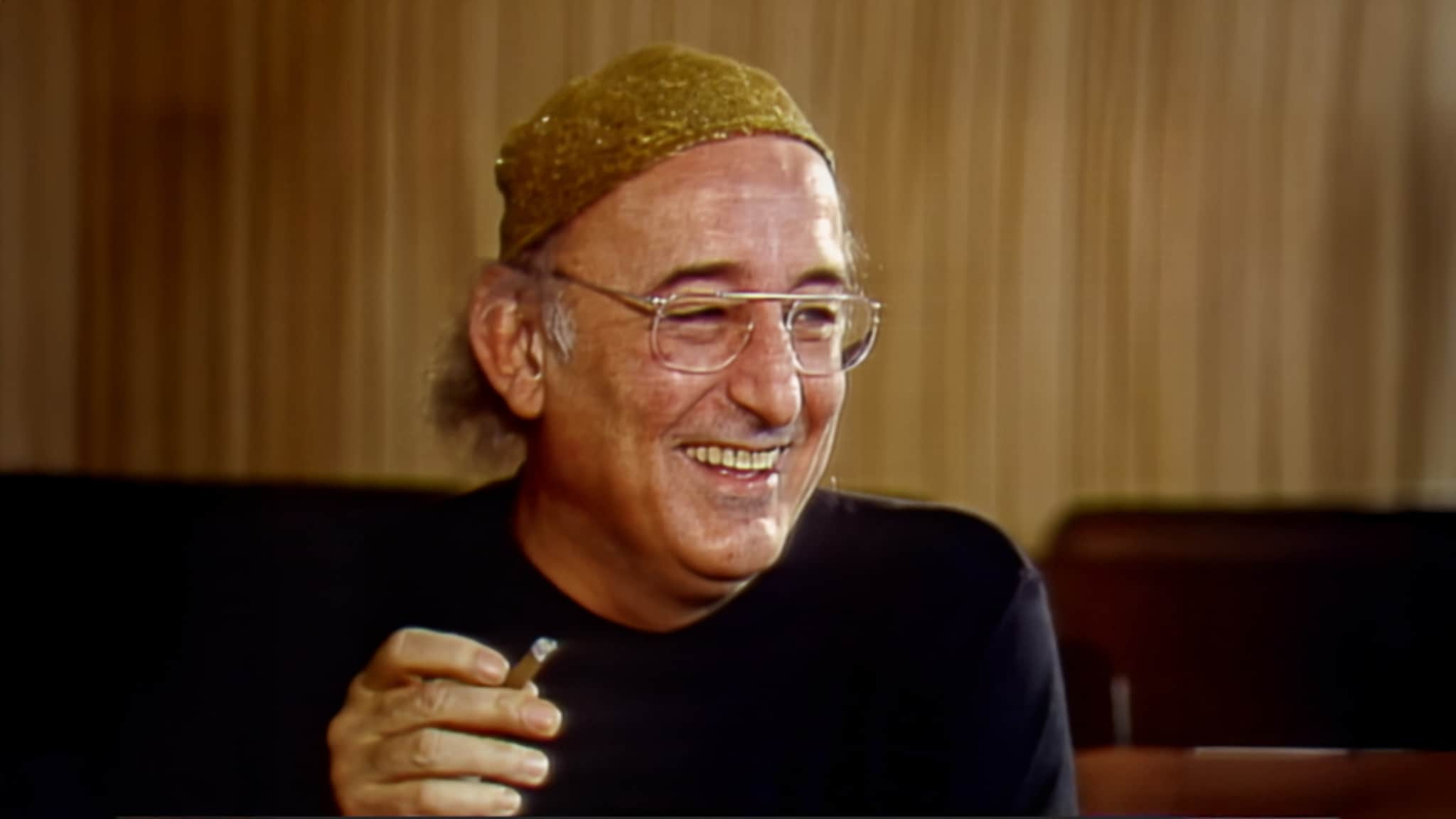

AboutFriedrich Gulda

Some people just don't fit the mold. Friedrich Gulda (1930–2000), for instance, was a figure who could ignite passions. To some, he was an apostate, dearly loved as an interpreter of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven's piano works, yet also greatly feared for his radical ideas, which, as a composer and jazz enthusiast, led him into the unsettling world of improvisation. To others, however, he was the quintessential boundary-crosser, one who opened up genre barriers to transcend the culturally imposed demarcation lines of performance and interpretation as comprehensively and in every direction as possible. But for everyone who ever heard him play, one thing is certain: Friedrich Gulda was one of the most significant pianists of the 20th century.

The young man started early. Born on May 16, 1930, in Vienna, he was just seven years old when he began private lessons with Felix Pazofsky. When Pazofsky had little left to teach him, Gulda continued his education until 1947 at the Vienna Music Academy with Joseph Marx (composition) and Bruno Seidlhofer (piano). From then on, he considered his artistic competence largely mature and set out to conquer international concert halls. He had already achieved significant successes, such as the first prize at the Geneva Competition in 1946. He soon made a name for himself as a Beethoven specialist, performing all 32 sonatas multiple times as a concert cycle, and was finally celebrated as a prodigy in New York's Carnegie Hall in 1950.

His comprehensive interpretive artistry often left reviewers struggling for words, as his musical understanding was as radical and unyielding as that of his genius colleague Glenn Gould. It's no coincidence that music critic Joachim Kaiser, in his piano anthology "Great Pianists of Our Time," places these two luminaries side by side and describes the Viennese master's style, with regard to his Beethoven interpretations, as "distinctly masculine, powerful, determined, resolute. Grand connections flow from him as if cast from a single mold, becoming clear, simple. Even at unleashed tempos, he never allows for imprecision. The left hand never just fumbles around, nor does the right hand toil aimlessly. His manual dexterity is extraordinary. Technically, he 'can' obviously do more than Schnabel or Kempf, than Fischer or even Richter. And he precisely understands what he can do."

Gulda enjoyed challenging himself. Already at 23, he caused a stir in the classical world by performing Beethoven's sonatas in chronological order, a project unusual and surprising in the 1950s. In 1968, he went into the studio for Decca and recorded his experiences with the works. It became a classic of interpretive culture, one that no pianist of stature can bypass without comment. Above all, however, in those very years, he began to warm to the then-young genre of jazz, not just intellectually but also playfully. He could become quite energetic when it came to conveying his musical preferences. It wasn't enough for him to be celebrated as the leading Mozart, Bach, or Beethoven interpreter of his generation, and so, from the mid-fifties, he emphatically tried to establish himself in the jazz scene as well. He jammed in New York clubs and played with greats like Dizzy Gillespie and Phil Woods, but due to his European classical background, he had a divergent understanding of musical form that differed significantly from the chorus-playing of the American school.

Gulda, in turn, felt underutilized, learned to play the baritone saxophone, flute, and several other instruments himself, composed extensively in various styles, and organized large concerts with changing repertoires and competitions, such as the famous 1966 competition, where no fewer than 116 jazz pianists from 24 countries competed. Two years later, he founded a school for improvisation in Ossiach, Carinthia. In 1969, he angered the dignitaries of the classical Viennese establishment when, during a speech at the presentation of the Beethoven Ring (which he returned a few days later), he denounced the outdated educational system. Thus, in the seventies, Gulda was both a sought-after classical interpreter and a busy scene guru, who was allowed to conceive and realize extraordinary concerts such as "Tales Of World Music" with traditional Italian songs by the "Nuova Compagnia di Canto Populare," Arabic impressions by Iraqi oud master Mounir Bashir, jazzy interludes by the Dizzy Gillespie Quartet, free improvisations by bassist Günther Rabl and percussionist Ursula Anders, and classical piano and harpsichord passages by Bach and Mozart in Salzburg in 1979. "What I strive for is the attempt to not only juxtapose different musical styles, which are usually relegated to dreadful categories like serious music, popular music, avant-garde, etc., but, more importantly, to present them to the same audience at the same event," Gulda said in an interview after the Salzburg project.

He had a similar idea three years later when he was among the initiators of the Munich Piano Summer. This festival, which still exists today, became a hub for cross-genre piano artistry and repeatedly offered Gulda the opportunity in the following years to present unusual and controversial programs, such as "Paradise Nights," which deliberately juggled with trivial stylistic elements. "In the seventies, he turned to completely different things and was no longer a concert pianist in the traditional sense. In the eighties, he was mainly interested in his own compositions, and in his last years, besides 'world champion' Mozart, he only occasionally played parts of his old repertoire," summarizes one of the master's sons, pianist Paul Gulda (*1961), about his father's later years. On January 27, 2000, Friedrich Gulda died unexpectedly in Weißenbach, Austria, leaving behind a comprehensive oeuvre, carefully re-released in collaboration with Deutsche Grammophon with the help of his long-time partner and estate administrator Ursula Anders, which is extraordinary in every respect.